What is gross domestic product (GDP)?

Gross domestic product (GDP) is the total monetary or market value of all goods and services produced within a country’s borders in a given period. As a general measure of total domestic production, it serves as a comprehensive assessment of a country’s economic performance. In Switzerland, GDP is also calculated per canton and per major region in Zurich (ZH), Central Switzerland (Bern, Fribourg, Solothurn, Neuchâtel, Jura), Northwestern Switzerland (Basel, Baselland, Aargau), the Lake Geneva region (Vaud, Valais, Geneva), Eastern Switzerland (Glarus, Schaffhausen, Appenzell Ausserrhoden, Appenzell Innerrhoden, St. Gallen, Graubünden, Thurgau), Central Switzerland (Lucerne, Uri, Schwyz, Obwalden, Nidwalden, Zug) and Ticino (TI).

GDP per capita

GDP per capita is a measure of the GDP per person in a country’s population. It indicates the amount of production or income per person in an economy and can represent the average productivity or the average standard of living. In a basic interpretation, GDP per capita shows how much economic production value can be attributed to each individual citizen. While GDP per country provides information about the economic performance of an entire country, GDP per capita can be used to compare the prosperity of a country.

GDP per capita is often analyzed together with more traditional measures of GDP. Economists use this indicator to gain an insight into the productivity of their own country as well as the productivity of other countries.

GDP per capita takes into account both a country’s GDP and its population. Therefore, it can be important to understand how each factor contributes to the overall result and how each factor affects per capita GDP growth. For example, if a country’s GDP per capita grows while its population remains the same, this could be the result of technological advances that produce more while the population remains the same. Some countries may have a high GDP per capita but a small population, which usually means that they have built a self-sufficient economy based on an abundance of specialized resources.

How the gross domestic product (GDP) is made up

The calculation of a country’s GDP includes total private and public consumption, government spending, investments, additions to private inventories, construction costs paid and the foreign trade balance. (Exports are added to the value and imports are subtracted).

The Federal Statistical Office calculates GDP using two approaches:

GDP according to the production approach = production value – intermediate consumption + taxes on products – subsidies on products

GDP according to the expenditure approach = consumer spending + gross investments + exports – imports

Of all the components that make up a country’s GDP, the foreign trade balance is particularly important. A country’s GDP tends to increase when the total value of goods and services that domestic producers sell abroad exceeds the total value of foreign goods and services that domestic consumers buy. When this is the case, we speak of a trade surplus. When the reverse situation occurs – when the amount that domestic consumers spend on foreign products is greater than the total amount of what domestic producers can sell to foreign consumers – it is called a trade deficit. In this situation, a country’s GDP tends to fall.

Types of gross domestic product

GDP can be calculated on either a nominal or real basis, with the latter taking inflation into account. Overall, real GDP is a better method of expressing long-term national economic performance.

Nominal GDP

Nominal GDP is an assessment of economic production in an economy that includes current prices in its calculation. In other words, it does not take into account inflation or the extent of price increases, which can inflate the growth figure. All goods and services counted in nominal GDP are valued at the prices at which they are actually sold in a given year.

Nominal GDP can be used, for example, to compare different quarters of production within the same year. When comparing the GDP of two or more years, real GDP is used. The reason for this is that adjusting for the influence of inflation makes it possible to focus exclusively on the respective volume when comparing the different years.

Real GDP

Real GDP is an inflation-adjusted measure that reflects the quantity of goods and services produced by an economy in a given year, with prices held constant from year to year to separate the effects of inflation or deflation from the trend in production over time. Since GDP is based on the monetary value of goods and services, it is dependent on inflation. Rising prices tend to increase a country’s GDP, but this does not necessarily reflect a change in the quantity or quality of goods and services produced. So if you only look at the nominal GDP of an economy, it can be difficult to tell whether the figure has increased as a result of a real expansion in production or simply because prices have risen.

Economists use an inflation-adjusted approach to determine the real GDP of an economy. By adjusting output in a given year for the price levels that prevailed in a reference year, known as the base year, economists can offset the effects of inflation. In this way, it is possible to compare a country’s GDP from one year to the next and see whether there is real growth.

Real GDP is represented using the price difference between the current year and the base year. For example, if prices have risen by 5 % since the base year, the inflation factor would be 1.05 (= 5 % + 1). Nominal GDP is divided by this inflation factor to give real GDP. Nominal GDP is usually higher than real GDP because inflation is usually a positive number. Real GDP takes into account changes in market value and thus reduces the difference between production figures from year to year. If there is a large discrepancy between a country’s real GDP and nominal GDP, this can be an indicator of significant inflation or deflation in the respective national economy.

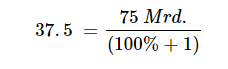

For example, let’s assume that a country had a nominal GDP of 50 billion in 2010. In 2020, the nominal GDP of this country has grown to 75 billion. In the same period, prices have also risen by 100 %. If you only look at nominal GDP in this example, the economy appears to be performing well. However, the real GDP would only be 37.5 billion, which shows that in reality, adjusted for purchasing power, there was an overall decline in real economic output during this period. The calculation is as follows:

How to use GDP when investing

Experienced investment professionals monitor GDP as it provides a reference for decision making. The corporateearnings and stocks data in the GDP report is a helpful resource for investors as both categories show overall growth during the period; the corporate earnings data also shows pre-tax profits, operating cash flows and breakdowns for all major sectors of the economy. Comparing the GDP growth rates of different countries can play a role in asset allocation and help decide whether and in which fast-growing economies to invest abroad.

An interesting metric that investors can use to get a feel for the valuation of a stock market is the ratio of total market capitalization to GDP, expressed as a percentage. The closest equivalent in terms of stock valuation is a company’s market capitalization to total sales (orturnover), which in stock terms is the well-known price-to-sales ratio.

Just as stocks in different sectors trade at very different price-to-sales ratios, different nations trade at very different market capitalization-to-GDP ratios. For example, according to the World Bank, the US had a market capitalization to GDP ratio of almost 165% in 2017 (the latest year with figures available), while China had a ratio of just over 71% and Hong Kong a ratio of 1274%.

However, the usefulness of this ratio lies in comparing it with historical values for a particular nation. For example, the US had a market capitalization to GDP ratio of 130% at the end of 2006, which fell to 75% by the end of 2008. In hindsight, these areas represented significant overvaluation and undervaluation for US equities respectively. Such special situations can be used by experienced asset managers to invest while the broad mass of investors withdraw from a market.