The definition of inflation

Inflation is the decline in the purchasing power of a particular currency over time. A quantitative estimate of the rate at which the loss of purchasing power occurscan be represented by the increase in the average price level of a basket of selected goods and services in an economy over a given period of time. The increase in the general price level, often expressed as a percentage, means that one Swiss franc, for example, can effectively buy less than in previous periods.

The opposite of inflation is called deflation, which means that the purchasing power of money increases and prices fall.

What inflation means

While it is easy to measure the price changes of individual products over time, human needs go far beyond one or two such products. People need a wide and diversified range of products and a variety of services to live a comfortable life. These include goods such as food, metals and fuel, utilities such as electricity and transportation, and services such as healthcare, entertainment and labor. Inflation aims to measure the overall impact of price changes for a diversified range of products and services and allows the increase in the price level of goods and services in an economy over a period of time to be represented by a single measure.

When a currency loses value, prices rise and fewer goods and services can be purchased. This loss of purchasing power has an impact on the general cost of living, which ultimately leads to a slowdown in economic growth. Economists agree that persistent inflation occurs when a country’s money supply growth exceeds economic growth. To avoid this, the Swiss National Bank (SNB), for example, then takes the necessary measures to control the supply of money and credit in order to keep inflation within permissible limits and keep the economy running.

Monetarism is a popular theory that explains the relationship between inflation and the money supply in an economy. For example, after the Spanish conquest of the Aztec and Inca empires, massive amounts of gold and especially silver flowed into the Spanish and other European economies. As the money supply increased rapidly, the value of money fell, contributing to rapidly rising prices.

Inflation is measured in different ways depending on the type of goods and services under consideration and is the opposite of deflation, which indicates a general fall in the prices of goods and services when the inflation rate falls below 0%.

Causes of inflation

An increase in the money supply is the main cause of inflation, and this can be triggered by various factors in the economy. The money supply can be increased by the monetary authorities either by printing more money and issuing it to citizens, by devaluing (reducing the value of) the legal tender, or (most commonly) by creating new money as reserve account balances through the banking system by buying government bonds from banks on the secondary market. In all these cases of money supply expansion, money loses its purchasing power. The mechanisms by which this leads to inflation can be divided into three types: Demand-sideinflation (demand-pull), cost-side inflation (cost-push) and built-in inflation (built-in).

Demand-side inflation effect (demand-pull effect)

Demand-side inflation occurs when an increase in the supply of money and credit causes the overall demand for goods and services in an economy to rise faster than the economy’s production capacity increases. As individuals have more money at their disposal, positive consumer sentiment leads to higher spending, and this increased demand drives up prices. This creates a demand-supply gap with higher demand and less flexible supply, which leads to higher prices.

Cost-side inflation effect (cost-push effect)

Cost-side inflation is a price increase that occurs across the means of production in the production process. When additional money and credit flows into the commodity or other goods markets, and especially when this is accompanied by a negative economic shock to the supply of the main commodity, the cost of all types of intermediate goods rises. These developments lead to higher costs for finished goods or services and are reflected in rising consumer prices. For example, if an expansion in the money supply leads to a speculative boom in oil prices, the cost of energy for all types of uses can rise and contribute to rising consumer prices, which is reflected in various measures of inflation.

Built-in inflation (built-in effect)

Built-in inflation is related to adaptive expectations, i.e. the idea that people expect current inflation rates to continue in the future. When prices for goods and services rise, workers and others expect them to continue to rise at a similar rate in the future and demand higher wages to maintain their standard of living. Their increased wages lead to higher costs for goods and services, and this wage-price spiral continues as one factor induces the other and vice versa.

Built-in inflation (built-in effect)

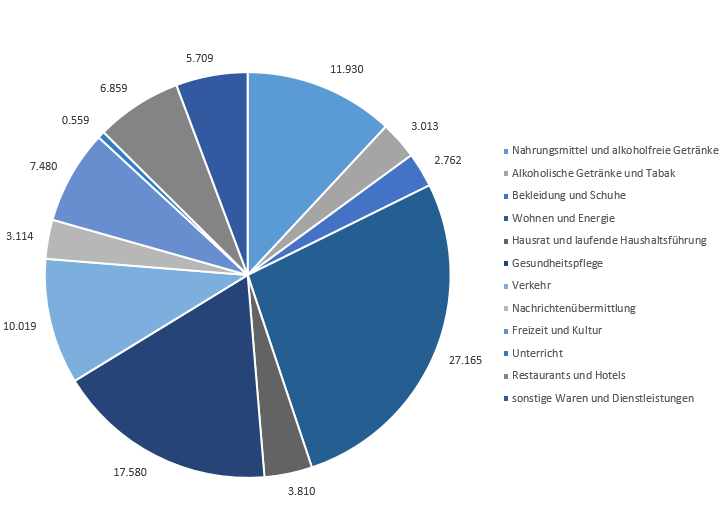

In Switzerland, price trends are calculated using the national consumer price index (CPI). This was composed as follows for 2021, for example:

LIK basket of goods and weights, 2021

Source: based on FSO – National Consumer Price Index 2021

According to the Federal Statistical Office (FSO), the CPI is calculated using a basket of goods. This basket contains the 12 most important expenditure categories, which should contain the most important household expenditure and are weighted accordingly. This allows the prices of these goods and services at a specific point in time to be compared with the prices at the base date and conclusions to be drawn as to how much the respective prices have risen within a year, for example. These prices are then weighted and combined to produce the national consumer price index (CPI). If the CPI has risen, this is known as inflation, i.e. one Swiss franc buys fewer goods and services a year later than it did a year earlier. Purchasing power has therefore fallen. If it has fallen, this is deflation and one Swiss franc buys more goods and services than a year ago. Purchasing power has risen.

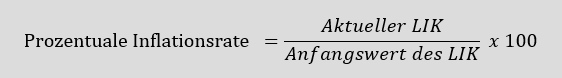

The formula for calculating inflation

The price index survey mentioned above can be used to calculate the value of inflation between two specific months (or years). Mathematically, this calculation is very simple and can be calculated as follows:

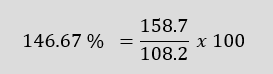

For example, according to the Federal Statistical Office, the CPI was 108.2 in 1986 and 158.7 in 2020. The percentage inflation rate from 1986 to 2020 was therefore as follows

This corresponds to an annual inflation growth rate of around 1.13 % per year over the 34-year period from 1986 to 2020.

Advantages and disadvantages of inflation

Inflation can be seen as either a good thing or a bad thing, depending on which side you are on and how quickly the change occurs.

People who own tangible assets that are priced in a currency, such as real estate or inventory, may be happy to see some inflation as it increases the price of their assets, which they can then sell at a higher rate. However, the buyers of such assets may not be happy about inflation as they will have to spend more money. Inflation-indexed bonds are another popular way for investors to profit from inflation.

On the other hand, people who hold currency-denominated assets such as cash or bonds do not like inflation either, as it erodes the real value of their holdings. Investors who want to protect their portfolio from inflation should consider inflation-hedged asset classes such as gold, commodities and real estate investment.

Inflation encourages speculation both by companies in risky projects and by private individuals in company shares, as they expect better returns than inflation. An optimal level of inflation is often propagated to encourage spending rather than saving to some extent. If the purchasing power of money declines over time, then there may be a greater incentive to spend money now rather than save. This can increase spending, which can boost economic activity in a country. It is assumed that a balanced increase keeps the inflation rate in an optimal and desirable range.

High and strongly fluctuating inflation rates can impose major financial burdens on an economy. Companies, employees and consumers have to take the effects of generally rising prices into account when making buying, selling and planning decisions. This introduces an additional source of uncertainty into the economy as they may misjudge the future rate of inflation. Time and resources spent researching, estimating and adjusting economic behavior to the expected rise in the general price level, rather than real economic fundamentals, inevitably represents a cost to the economy as a whole.

Even a low, stable and easily predictable inflation rate, considered by some to be optimal, can cause serious problems in the economy because it depends on how, where and when the new money enters the economy. Whenever new money and credit enters the economy, it ends up in the hands of certain individuals or businesses, and the process of adjusting the price level to the new money supply is set in motion as they spend the new money and it circulates through the economy from hand to hand and account to account.

Along the way, it first drives up individual prices and later drives up others. This sequential change in purchasing power and prices means that the process of inflation not only raises the general price level over time, but also distorts relative prices, wages and yields. Economists generally agree that distortions of relative prices away from their economic equilibrium are not good for the economy.

Inflation control

The important task of the central bank of a country or economic area is to keep inflation under control. This is achieved through monetary policy measures, e.g. a central bank determining the volume and growth rate of the money supply.

In Switzerland, the Swiss National Bank’s monetary policy objectives include the primary goal of price stability. Price stability – or a relatively constant level of inflation – allows companies to plan for the future, as they know what they can expect. The SNB believes that this is an “essential prerequisite for growth and prosperity”.

The SNB can also take extraordinary measures in extreme circumstances, such as the introduction of a minimum exchange rate of CHF 1.20 per euro after the financial crisis from September 2011 to January 2015 and the introduction of negative interest rates in June 1972 to November 1979 and again from November 2014 to the present (2021). Other central banks have also taken extraordinary measures in the past. For example, the US Federal Reserve kept interest rates close to zero after the 2008 financial crisis and pursued a bond-buying program called Quantitative Easing (QE). Some critics of the program claimed that it would cause a surge in US dollar inflation, but inflation peaked in 2007 and steadily declined over the next eight years. There are many complex reasons why QE did not lead to inflation or hyperinflation, but the simplest explanation is that the recession itself was a very pronounced deflationary environment and quantitative easing supported its effects.

Both the US Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank pursued aggressive quantitative easing after the financial crisis (2007 to 2008) to counteract deflation in the eurozone, and negative interest rates were introduced in some places for fear that deflation would take hold in the eurozone and lead to economic stagnation. In addition, countries with higher growth rates can cope with higher inflation rates. India’s target is around 4 %, while Brazil is aiming for 4.25 %.